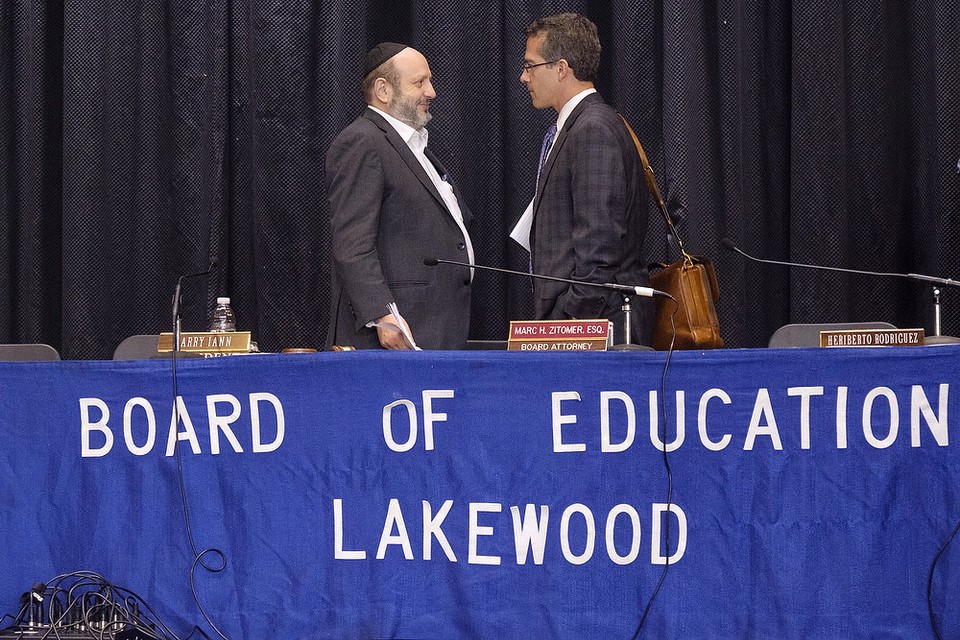

Today the Star-Ledger reports that Barry Iann, the President of the Lakewood Board of Education, quit on Monday night. He’s giving up, he says, because there’s too much bad press and there’s not enough funding. He’s right about the district’s fiscal mess; while Lakewood is indeed under-funded, much of the liability for the annual shortfall, about $15 million per year, falls squarely on the Board because it participates in the practice of paying tuition to schools that, under state law, don’t actually qualify as schools.

Board presidents rarely resign. Bad press is part of the package and so is budgetary strain. I know — I was a board president for nine years. A burnt-out officer might step aside and resume the responsibilities of a plain old board member. But quitting? Doesn’t happen. Unless there’s more to the story.

I think that there is.

Regular readers of this blog know that Lakewood Public Schools is trapped in a culture of fear and corruption, especially regarding the privileged position gifted to ultra-Orthodox students. (See here for more on this.) While the mostly Latino and low-income traditional students get the short end of the stick in regards to special and general education programming, the district habitually pays tuition for special education students in ultra-Orthodox yeshivas. With an annual operating budget of about $127 million, Lakewood will spend $32 million this year in tuition, a staggeringly disproportionate amount, the highest tuition bill in the state.

And many of those placements are illegal.

The New Jersey Department of Education’s voluminous regulations includes this one, 18A:38-25:

Every parent, guardian or other person having custody and control of a child between the ages of six and 16 years shall cause such child regularly to attend the public schools of the district or a day school in which there is given instruction equivalent to that provided in the public schools for children of similar grades and attainments or to receive equivalent instruction elsewhere than at school.

Today’s question: do ultra-Orthodox yeshivas qualify as schools that “give instruction equivalent to that provided in the public schools for children of similar grades and attainments”? If they do, then the Board’s approval of placements is within the law. If they don’t, then the Board is breaking the law.

Which is it?

Let’s look at page 22 from the Lakewood Board of Education Minutes from this past January’s public meeting. (These items appear almost every month but I’m trying to be efficient.) Here the Minutes lists monthly tuition payments for approved placements in out-of-district schools. In January these included Bais Rivka Rochel, Bais Faiga School for Girls, and Yeshiva Orchos Chaim. The last one, Orchos Chaim, will charge about $11,000 per month for one child and about $7,000 per month for another.

Will these two children with disabilities receive “instruction equivalent for those of similar attainments” in secular schools?

That’s a hard question to answer because Lakewood’s yeshivas, like most ultra-Orthodox ones, tend to be secretive to the secular public. However, a recent interview with a brave young man named Jay Fishman gives us some clues.

Jay, who used to be known as Chaim, grew up in Borough Park, a section of Brooklyn that is home to many Haredi ultra-Orthodox Jews, just like Lakewood. He told his story to an interviewer from a non-profit called Yaffed, which defines its mission as “improving educational curricula within ultra-Orthodox schools” and “encouraging elected officials, Department of Education officials and the leadership of the ultra-Orthodox world to act responsibly in preparing their youth for economic sufficiency and for broad access to the resources of the modern world.”

Jay’s ultra-Orthodox yeshiva adheres to this schedule::

- Religious instruction from 9 a.m. until 4 p.m.

- Secular instruction from 4 p.m. to 5:30 p.m..

Secular instruction — what children receive in public schools all day — begins in Jay’s yeshiva in 2nd or 3d grade. He was 8 or 9, he says, when he was first introduced to his ABC’s by his teacher, who taught the class in Yiddish. English studies ended with spelling; Jay rues the lack of vocabulary. When he asked the teacher what a word meant, the teacher would reply, “I’ll ask my wife tonight.” (Girls have far more access in their yeshivas to secular instruction because they’re expected to get a job to support their husbands, who devote themselves to Torah study.) Math instruction for Jay also began in 2nd or 3d grade, where he progressed with the other boys up to division. At no time was he exposed to science, social studies, art, or physical education.

At age 11, he and his classmates began a new schedule, arriving at school at 7:45 a.m., where “we prayed together, had breakfast, and then followed the same schedule” as before. During his last year of middle school, the secular equivalent of 8th grade, school lasted until 6:20 p.m. and, he explains, “the hour and a half of secular education was taken away. No English or math whatsoever.”

In 9th grade, he began the yeshiva’s high school in Red Hook where the school day began at 7 a.m. and lasted until 8 p.m. “There were no secular studies. We only communicated in Yiddish and Hebrew. The only people who weren’t Hasidic (a branch of Haredi) were the janitors.”

Jay continues, “we never learned writing. We learned spelling but never vocabulary. We never learned how to write a paragraph. We never learned the word “molecule.” My childhood friends have never heard that word…I was 15 years old and grew up in New York City and didn’t really know English. The only math I could do was division.”

The interviewer asks him what happened when city and state inspectors would visit. “If the government came in, would there be any changes that day?”

Jay replies, “Absolutely! When the inspectors would come in, everyone would change. The school always knew about the visits beforehand. One time the inspectors came and we had such different food, so much better. Another time we had a carnival. We had never had a carnival.” He muses, “the legal system requires me to to go to a school that breaks the law.”

Jay might as well be describing Lakewood’s Orchos Chaim, listed on those January Board Minutes, which serves about 800 boys K-8. But does it qualify as a “school” under 18A:38-25? Does it offer “instruction equivalent to that provided in the public schools for children of similar grades and attainments” or do the boys “receive equivalent instruction elsewhere than at school”? Is it legal for Lakewood to pay to attend?

The answer appears to be a resounding “no.”

While there is no information on the web beyond an address and phone number, the yeshiva has several youtube videos. Check this one out, part of a fundraiser for expansion costs. The principal, Rabbi Eli Schulman, explains how the mission of the school is to “focus on excellence,” specifically, “how can the davening take on more hashamayim.” (Translation: how can praying reach heavenly heights?) Another rabbi (all the teachers are rabbis, which can also be an honorific) exults, “when you walk in you feel the Yiddishkeit [Jewishness].” Another say, “we are working to create the next generation of am Yisrael [the people of Israel]” and another says “we have to be there for the needs of the rebbayim and Torah [teachers of Torah].”

While the rabbis speak, behind them we see classrooms filled with young boys learning their aleph-bet (Hebrew alphabet), davening, discussing Torah (the Jewish bible). The whiteboards and posters on the wall are all in Hebrew. The chatter is all in Yiddish. There is not a single shot of secular instruction. While it’s hard to tell from a video, I wasn’t able to identify a single boy with disabilities.

Yeshiva Orchos Chaim is a yeshiva just like Jay Fishman’s, almost entirely devoted to religious studies and entirely absent of “instruction equivalent to that provided in the public schools for children of similar grades and attainments.”

In other words, this Lakewood yeshiva does not meet the criteria, per DOE regulations, of a school.

How much tuition does Lakewood Public Schools pay for these non-schools? It’s hard to say. Two hundred Lakewood students attend the School for Hidden Intelligence (SCHI), which I’ve argued before is a special education yeshiva devoted, as well, to religious studies. If Lakewood played by the rules, how much would its deficit be reduced? How many more resources would be available to the non-Jewish students of color who get by on a paltry $13K a year — not much more than Lakewood is paying for one student at Orchos Chaim per month — and attend a high school where 7 percent of students reach grade-level proficiency in math?

Jay Fishman was able to compensate for his lack of access to non-religious education. Against his parents’ wishes, he left yeshiva in 9th grade and transferred, after a year of self-study and English language immersion, to a traditional NYC school. He just got accepted at the University of Pennsylvania, which he calls “an impossible dream” for his former classmates. “They are smart and motivated,” he says, “going to school 13 hours a day. But without a secular education you are crippled for life. And the teachers got the same education we got.”

The boys at Orchos Chaim or the other yeshivas in Lakewood, Jay would argue, are also “crippled for life.” And, for some of them, Lakewood pays the tab.

Board President Iann quit Monday. I don’t know why. But if he’s a man of integrity, it might be because he doesn’t want to be caught up in this inequitable and illegal mess.

8 Comments