When my husband Dennis and I were getting ready to move from upstate New York to a new home within a reasonable commuting distance to his office in Manhattan, we zeroed in on Mercer County in Central Jersey. After all, you can get to Penn Station in an hour on an express NJ Transit train, we’d be reasonably close to my family, and housing prices were more affordable than, say, Westchester or Connecticut. Of course, we had our heart set on Princeton, with its schools to die for. Our oldest was not yet three but we were thinking ahead!

We weren’t ready to buy — hadn’t come up with a down payment yet — but we were rarin’ to rent. One weekend in April we left our two little ones with my folks and met our real estate agent. We’re not picky, we told her: just two or three bedrooms, within walking distance to Princeton’s quaint “dinky” to the train station. (We had one car.) We could pay up to $1,000 a month, which we considered extravagant in comparison to our upstate rental.

Nada. Our agent gently allowed realty reality to impose itself. Then she drove us to Lawrence Township, six or seven miles south, where we found a rental within our price range (Dennis would catch a bus to the Trenton train station) and, eventually, a house to raise our growing family. We love it here, as much for its diversity as its gorgeous hiking trails. We wouldn’t want to live anywhere else.

But I know the difficulty of buying your way into one of the best school districts in the state, even for families who consider themselves solidly middle-class. So I read with chagrin this dispatch from Planet Princeton regarding the Princeton Board of Education’s proposal for a $137 million referendum in order to quench, as Superintendent Steve Cochrane said, “a desire to align learning spaces to learning goals.” If the referendum passes in a public vote, homeowners with a house assessed at the Princeton average of $837,000 will pay an extra $680 a year in debt service. That’s on top of next year’s school budget, which will increase by 3.63 percent, which adds another annual $159 in encumbrances for homeowners for a grand total of $839 per year.

Whoa! Lawrence recently passed its own referendum, $25 million (40 percent paid by the state) to make schools more secure from intruders, replace boilers, and air-condition some of our old buildings where temperatures sometimes reach 90 degrees in June and September. Lawrence homeowners — the average house costs

$284,000 — will pay about $85 a year in additional property taxes.

Princeton Board President Patrick Sullivan said, “[n]obody wants to build a palace, but on the other hand, Scarsdale, New York spends probably twice as much as we do on education. It’s a different kind of community obviously, but I think we are all working towards that goal.” (For the record, Scarsdale spends about $31,000 per year per pupil; Princeton spends about $25,000.)

It’s not clear that all community members share that ambition. At the most recent Board meeting, resident Kip Cherry said,“t

he middle class is being squeezed out of Princeton.” Mary Clurman worried about “the continuing trend of more modest homes being sold, knocked down, and turned into million dollar homes.”

Concurrently, and with a dash of irony, Princeton Township just received a ruling from State Supreme Court Justice Mary Jacobson that orders the township to build 753 new affordable housing units, a responsibility mandated by the

Mount Laurel Doctrine, a civil rights law that “recognizes that a municipality’s power to zone carries a constitutional obligation to do so in a manner that creates a realistic opportunity for producing a fair share of the regional present and prospective need for housing low- and moderate-income families.” (Within Mercer, all townships had already agreed to take on their fair share except for our two wealthiest, Princeton and West Windsor.) In the past, Princeton had evaded its responsibility by entering into (now-defunct) Regional Contribution Agreements that let them pay off Trenton to take on its affordable housing obligations. It can’t do that anymore.

The Jacobson court ruling represents a slight tear in N.J.’s fabric of local control that we wear like a magic cloak, one that precludes access to great schools for the hoi polloi.

As Peter Cunningham writes in today’s U.S. News and World Report,

Local control offers a legacy of racial segregation, funding inequity and academic mediocrity. In every important metric of success from student achievement to access to rigorous classes to high school and college completion, stubborn racial and economic gaps remain. The plain fact is that local control and quality control rarely go hand-in-hand.

Yet Princeton aspires to be a palace that gates out the great unwashed. How does the school leadership reconcile its vision of royalty with, courtesy of that Court ruling, a cohort of Cinderellas moving into town?

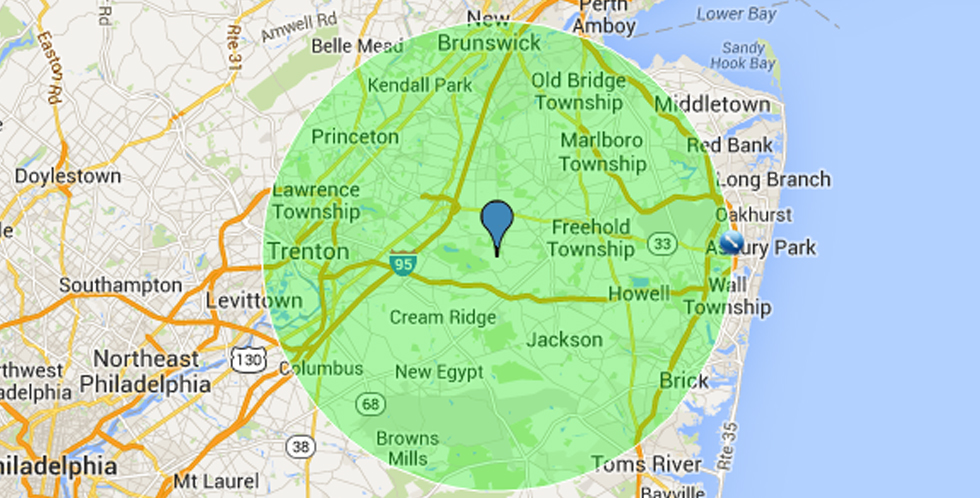

I don’t have any answers. All I know is that N.J. school inequity is driven by our fetishistic adherence to local control. Students in Trenton can’t attend Princeton schools, a mere 13 miles away. At the border of Lawrence and Trenton, if you live on one side of the street you send your kids to Lawrence schools and if you live on the other side of the street you send your kids to Trenton ones.

That feels like every kind of wrong to me.

It’s one thing for a town to have sky-high housing costs. It’s another to gate off schools and give keys to only those who can afford the tariff. No tweaking of the school funding formula will erase the inequities driven by local control. Five years ago Paul Tractenberg proposed several remedies, including developing “a system of very high-quality regional magnet schools that are good enough to attract students of all races and socioeconomic strata from multiple school districts” as well as creating county-wide districts, something I’ve advocated in the past. Dr. Tractenberg suggested we start with a pilot for Essex, our smallest county, which includes impoverished Newark nine miles from wealthy Millburn. I nominate Mercer’s nine school districts. Imagine: Trenton, Lawrence, and Princeton students go to school together, sharing course content, teachers, facilities, and all that goes into public education.

Yeah, I know. A politically impossible pipedream. They’re all our kids. Except when they’re not.

1 Comment