When the Newark Teachers Union (NTU) and the Newark Public Schools, under the superintendency of Cami Anderson, agreed in 2012 to a new contract that linked teacher pay to performance, AFT President Randi Weingarten said, “This agreement ensures that teacher voice, quality and experience are aligned with increased professionalism and better compensation.”

This past summer NTU President John Abeigon, when queried by a Chalkbeat reporter about those 2012 innovatives and upcoming negotiations for a new contract, said that the contractual reforms “failed” because “the district was not being run by educators. It was being run by corporate charter reformers.” When asked if he would try to keep any of the new provisions that differentiated teacher effectiveness far more specifically than in the past, he replied, “we’re going to be trying to negotiate them all away…Except for [performance pay]. We have no problem with getting more money into the pockets of our members.”

Is it true that the 2012 reforms, particularly changes to the teacher evaluation system, “failed”? Not according to a report released today by The National Council on Teacher Quality. NCTQ analyzed six teacher evaluation systems in a report called “Making a Difference: Six Places Where Teacher Evaluation Systems are Getting Results

.” The report examines six sites that have undertaken bold steps in innovating assessments of teacher effectiveness — Dallas Independent School District, Denver Public Schools, District of Columbia Public Schools, Newark Public Schools, New Mexico, and Tennessee — and rates the effectiveness of each system.

Guess what? Mr. Abeigon’s assertions to the contrary, Newark Public Schools teacher evaluation system is at the top of the class.

And it’s not just the money.

But let’s talk about the money. Under the system initiated by Anderson, continued by the last state-appointed superintendent, Chris Cerf, and now new Board-appointed superintendent Roger León (Newark assumed local control last year), teacher effectiveness is gauged by multiple measures and each teacher is graded on a four-point scale: Ineffective, Partially Effective, Effective, and Highly Effective. The pre-Anderson/Weingarten contract awarded the highest-paid teacher (with a Ph.D. a Master’s degree plus 30 credits, or a Bachelor’s degree plus 60 credits) $103,159 after 29 years, regardless of effectiveness. The current contract tops out at $100,531 after 18 years of teaching ($95,531 maximum base salary plus up to $5,000 in bonuses) for Highly Effective teachers.

In other words, the best teachers get more money faster.

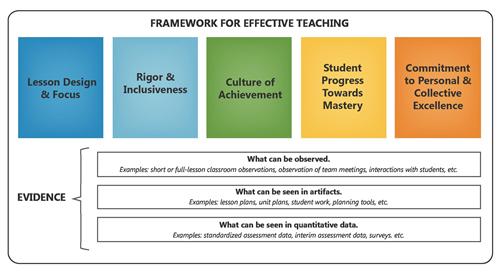

But, as Larisa Shambaugh, former Chief Talent Officer notes, the evaluation system is “more than a way to put teachers into buckets; it is for coaching, feedback and growth, and sometimes for exiting or promoting teachers.” Indeed NCTQ praises Newark’s system for the following reasons:

- The district gave the evaluation system a chance to work. While Newark saw students’ achievement decline initially after the new evaluation system was implemented, the district persevered and student achievement rose to the level it had been before and, in English, exceeded previous levels.

- Newark’s central office creates monthly reports that serve the dual purposes of providing principals with data on their progress completing evaluations and tracking the integrity of their ratings by showing their schools’ teacher ratings distribution compared to other schools’ ratings distribution. These reports allow principals, their supervisors, and the central office staff to examine the same data and have conversations around these data.

- Newark invested substantial resources when the system was first implemented to train principals on what the language of the evaluation framework meant, what to look for when observing teachers, and how to reliably rate teachers. Now, the district maintains this consistency by holding a brief retraining every summer.

- Newark offers teachers a rebuttal process if they disagree with their evaluation rating.

Of course, there’s always room for improvement. NCTQ suggests that the evaluations include student surveys of teachers to “provide another layer of understanding about a teacher’s performance.”

The report also asks a salient question: Is there evidence that the new system is helping increase student learning?

The answer appears to be “yes.”

Principals and supervisors, according to NCTQ, are using the evaluation system with integrity. In the most recent round, 4 percent of teachers were rated Ineffective, 10 percent were Partially Effective, 76 percent were Effective, and 11 percent were Highly Effective, a far more granular analysis than the state’s claim that 98 percent of NJ teachers are effective. The system also aids retention of Newark’s best teachers and attrition of the worst: “[T]he retention rate for highly effective teachers is 96 percent in the fifth year of the evaluation system” and 49 percent of ineffective teachers voluntarily leave Newark Public Schools.

Concurrently, student academic growth is increasing, although not fast enough for anyone. From the report: “Newark Public Schools’ students are growing at a faster rate in English language arts compared with their peers across New Jersey” although “there is no significant net change in math.” But another point of evidence of impact is that “the district has a higher student enrollment now than at any other time in its recent history, a sign of renewed confidence in Newark schools.

And, finally, NCTQ points at the primary reason for the growth in student achievement: “the district’s decision to move students out of lower- to higher-achieving schools.” This correlates with the recent Harvard report (see my summary here

) that found that “62 percent of the gain in achievement growth in English was due to students leaving less effective schools and moving to more effective schools,” primarily charter schools that now serve 40 percent of Newark public school students.

NTU President Abeigon’s sentiments to the contrary, NCTQ President Kate Walsh comments, “Our analysis suggests that moving forward with teacher evaluation systems presents students and teachers with a huge opportunity.” Let’s hope the NTU negotiating committee members keep their eyes on the prize: the academic growth of Newark schoolchildren.

1 Comment