I was chatting with a teacher from Asbury Park High School, who wishes to remain anonymous. We were talking about the impact of the then-Asbury Park Superintendent, now-Education Commissioner Lamont Repollet’s decision to create a system, “The 64 Floor,” that makes it impossible for students to fail a course. (Repollet owned up to this practice during a New Jersey Senate Budget and Appropriations Committee hearing and justified it by claiming that “teachers weaponize grades.”) Now it’s automated: If a teacher enters, say, a 45 for a student’s grade, the computerized platform automatically changes it to a 64.

In addition to this practice of artificially raising student grades and, thus, the high school graduation rate, Repollet made another change: Teachers at Asbury Park have told me that, at least at the high school, principals no longer suspend students. This policy has been continued by Repollet’s chosen successor, Superintendent Sancha Gray. Now when teachers write discipline referrals, the principals, following directives from the top, mostly ignore them and send the kids back to class.

Is this a good thing or a bad thing? I suspect it all comes down to leadership and implementation.

There are plenty of studies that show correlations between suspensions and the school-to-prison pipeline, especially for boys of color. (At Asbury Park High, 98% of students are Black or brown.) The Obama Administration addressed the disproportionality in discipline in a 2014 “Dear Colleagues” letter, which noted that three times as many Black students are suspended as white students when committing the same infractions. Instead, schools should offer ways to detect implicit biases and promote techniques aligned with restorative justice. Last year current U.S. Education Secretary Betsy Devos rescinded those guidelines (I criticized her for doing so here) but schools’ awareness of disproportionality remains.

According to two new studies, however, teachers think we’ve gone too far, especially when complex restorative justice techniques are inadequately implemented.

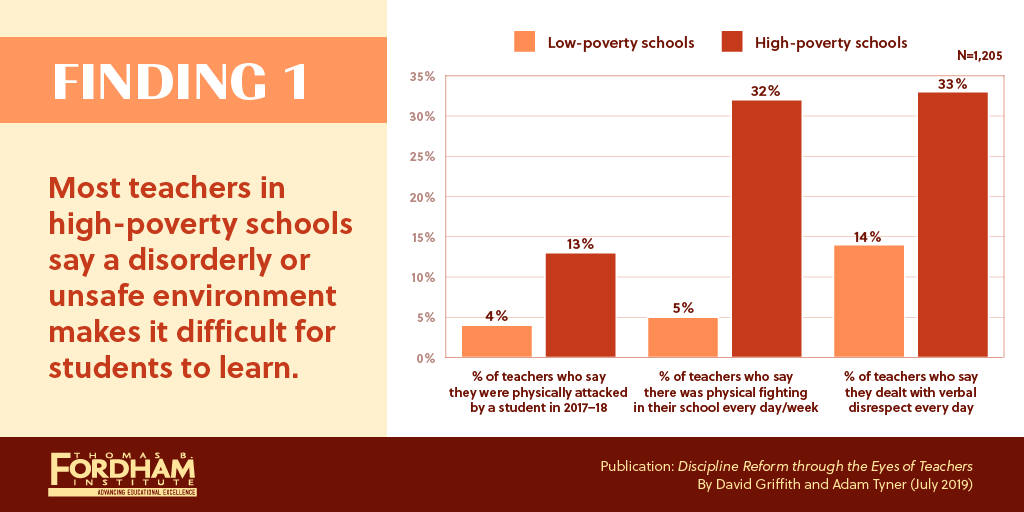

That’s the take from the Fordham Foundation, which just issued a report called “Discipline Reform Through The Eyes of Teachers,” by David Griffith and Adam Tyner. In the Forward, Amber Northern and Mike Petrelli write,

Compared to their peers in low-poverty schools, teachers in high-poverty schools report higher rates of disciplinary incidents, such as verbal disrespect and physical fighting. In general, teachers say that disciplinary protocols are inconsistently observed and that the recent decline in suspensions is at least partly explained by higher tolerance for misbehavior or increased underreporting. Although they see value in new approaches to combating student misbehavior, most teachers also say that suspensions are appropriate in some circumstances—and that some chronically disruptive students shouldn’t be in their classrooms at all. Finally, many black teachers say that “exclusionary discipline” should be used more often—despite the likely costs for students who misbehave and their belief that disciplinary consequences are racially biased.

The Fordham report concludes that restorative justice is not working well (or is not being implemented well), forcing teachers to keep disruptive kids in classrooms, rather than suspending them. This, many of them report, is harming the academic growth of non-disruptive kids and making the work of teaching that much harder. In particular, “many African American teachers (including half of those in high-poverty schools) say out-of-school suspensions should be used more often.”

In other words, a well-intentioned set of regulations designed with civil rights and equity in mind, has led to unintended consequences. Here’s the view of a teacher quoted in the study:

Restorative justice has led to a huge decrease of suspensions. I fully understand the arguments for this approach. However, I strongly feel that this approach is failing students, particularly students of color, because it is reinforcing the idea that there are little or no consequences for negative behavior. Things do not work like this in the real world, outside of school. So it is better to teach students that there are real consequences for misbehavior at a young age, rather than have them learn that the hard way with the criminal justice system.

A poll released this week by PDK called “Frustration in the Schools: Teachers Speak Out on Pay, Funding, and Feeling Valued,” includes this: “Among public school teachers, 64% say discipline in their own school is not strict enough.”

That’s what the teacher in Asbury Park told me (and he wasn’t the only one).

Let’s look at Asbury Park High School’s rate of suspensions over the years since the Obama guidance. (Note: districts self-report this data to the DOE and we don’t yet have information for the 2018-2019 school year.)

2015-2016: 100% of students suspended. (Again, this is self-reported and seems unlikely but that’s what the School Performance Report says.)

2016-2017: 34% of students suspended.

2017-2018: 18% of students suspended.

If what the teachers at Asbury Park High School are telling me is correct — and they have been very reliable — the rate of suspensions for 2018-2019 will be even lower. But is this lower rate proof of a successfully-implemented restorative justice program or another version of the 64 Floor? Is Asbury Park lowering suspensions under the banner of restorative justice in order to create the pretense of progress?

Example: One Asbury High School teacher (not the source at the top of this post) told me about an incident where a student started throwing chairs at other students; she was so fearful for the other students that she took them into the hallway to protect them. When she wrote up a discipline report for the chair-throwing student, the principal just sent him back to class.

Now, from what I was told, there was an initial attempt in Asbury Park to implement a district-wide effective restorative justice program, a monumental task requiring a fundamental cultural and pedagogical shift in approaching infractions. This requires intensive professional development in restorative justice techniques, full teacher buy-in, and consistent leadership.

To lead this initiative, in July 2018 the Asbury Park School Board promoted a counselor, Alisha DeLorenzo, to “Social Emotional Learning Coordinator,” a 12-month position at $140,000. But, two teachers told me, “we never saw her, she showed up at the school maybe every other week.” (She did find time for the trip with then-Superintendent Repollet to Ghana.) Eleven months later Ms. DeLorenzo resigned from Asbury Park to take a position at Garden State Equality. The restorative justice initiative was taken over by Dr. Kristie Howard, who became Director of Student Services when Repollet appointed Carolyn Marano to the DOE in May 2018. (Howard went to Ghana but Marano wasn’t on the guest list.) I’m not sure when Howard left but right now the Asbury Park district website lists Clement Bradley as Intermim Director of Special Services.

Perhaps the teachers in the Fordham and PDK studies who look dimly at restorative justice initiatives are responding to poorly implemented and inconsistently-led restorative justice systems, just like the teachers at Asbury Park High School.

On Monday Comm. Repollet had an op-ed in NJ Spotlight. He wrote,

Schools in the Garden State are working to ensure that students of color are not disproportionally represented in special education programming and, conversely, that they have access to gifted and talented programs. Schools are having courageous conversations about race and bias; developing equity councils and teams; implementing culturally relevant curricula; exploring alternatives to traditional disciplinary practices; and implementing culturally responsive teaching.

That sounds so good, so fair, so just. And yet all the pretty words in the world mean nothing if the hard work of restorative justice is erratically and/or poorly implemented. If so, then all you have are frustrated teachers, disrupted learning, and unsafe classrooms.