These are hard times. We’ve all had to make changes in the way we live, learn, and work. It’s no surprise that state education bureaucracies are struggling to, one extent or another, in implementing effective online instruction for students.

But you wouldn’t know that from New Jersey Education Commissioner Lamont Repollet. In this interview with John Mooney of NJ Spotlight he addresses the “character of our workforce,” saying, “I salute you, because you have been our students’ rock. You have been teacher, parent, educator.”

I’m not sure what that means except, of course, our teachers, parents, and students are doing the best they can. But how does New Jersey’s DOE response compare with the rest of American states? According to this dashboard, pretty poorly.

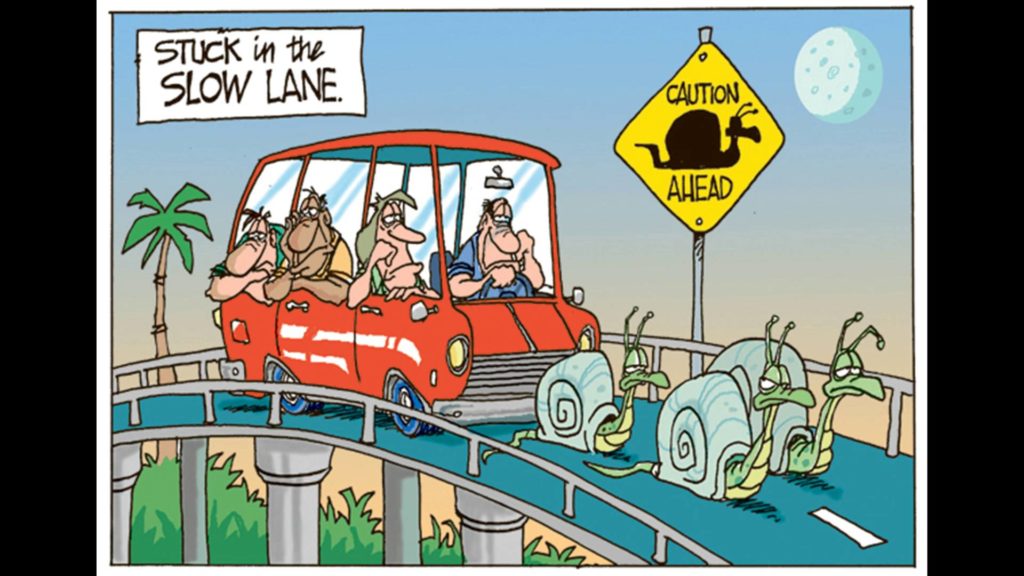

ERN (Education Reform Now) continuously updates its analyses of how successfully states are adjusting to remote instruction. States are rated on a rubric that goes from the worst implementation — 25 miles an hour — to the best, 65 miles an hour. Currently 29 states are speedily moving forward at 65 mph, 14 states are close behind at 50 mph, 7 are in the slow lane at 35 mph, while one (Maryland) is hardly moving at all.

New Jersey is in the slow lane. While speedier states are providing districts “with guidance/templates for distance learning, access to professional development for educators, providing instructional resources to families, issuing “clear guidance” for special education, and addressing the digital divide,” NJ’s team is missing some of those essential ingredients for successful online instruction. (You can read the full report here.)

But you wouldn’t get that impression from the Spotlight interview which included Repollet, Assistant Commissioner for Academics Linda Eno, and Assistant Commissioner for Field Services Abdul Saleem Hasan.

When Mooney asks Repollet “how your job changed that day in March when you knew schools would be closing and New Jersey would move to statewide home schooling,” Repollet replies, “the first thing we had to do is shift our mindset to understand that we’re no longer going to be in a brick-and-mortar school setting. And so we went from governing and overseeing to moreso [sic] facilitating the transition to online learning.” Eno chimes in, “We started with a large-scale survey to understand exactly who didn’t have devices.”

Repollet adds, “what I would love … to come out, is that ‘wow,’ in 20 days we put up a virtual school system in the state of New Jersey. “ He says the DOE had to pivot to “understanding what are the needs of our students” and “I think we always try to stay one step ahead.”

Shift your mindset to online learning? Start a large-scale survey? Stay one step ahead? Repollet and Eno must have forgotten that in 2016 the DOE (under the Christie Administration) started Future Ready Schools NJ, a state-funded grant program to implement a “digital learning environment.” If Repollet’s team had actually paid attention to this program (I’ve been told they didn’t) we wouldn’t have 100,000 students without one-on-one devices because they could have gotten school-level data on access.. Senator Teresa Ruiz, chair of the Senate Education Committee, nails it when she says, “why in this day and age do we not have every child connected to the internet? It’s our responsibility to connect them.”

And only now the DOE is thinking about “the needs of our students?” And only now “educators are using technology, which some of them may even have never had professional development on”? What the heck has Repollet’s team been doing for the last three years?

I spoke to a DOE staff member who will remain anonymous. She was incredulous at Repollet and Eno’s remarks in the Spotlight interview, telling me “the only way the Department can admit to surprise over this scenario…is because the thinking there is as in-the-box and traditional as the days when teachers couldn’t be married and lunch pails were stashed in cold water wells.”

Mooney asks about Repollet waiving all standardized testing, teacher evaluations, and high school graduation assessments. He replies,

We have always been in the business of educating students. But lately, education has been the business of education. I think now we’re getting back to the heart and soul, which is student learning. So when we take all those unwanted burdens and problems you have to do. Now we’re getting down to the core of what we need to do in regard to student learning.

That’s fine. It’s unreasonable to expect that students will take standardized tests since few are learning new material during school closures and, anyway, they’re home. It’s unreasonable to tie student growth to teacher evaluations this year (although at this point the link is meaningless).

But how is accountability — those “unwanted burdens and problems you have to do” — unconnected to student learning? How do you know students are learning if you don’t measure their progress?

Ah, but Repollet doesn’t want to measure the progress. That’s why he came up with the 64 Floor.

And let’s be frank: In June more students than ever will receive high school diplomas that do not signify readiness for college or careers. More students will move on to the next grade without the knowledge they need to be academically successful or they’ll repeat the grade (which seems politically unlikely because that’s the “business of education”).

It didn’t have to be this way. At KIPP NJ’s Newark schools, which serve 4,800 students, Executive Director Joanna Belcher started preparing early for the presumed closures, handing out laptops to 65% of students and providing wifi hotspots to those without internet at home. In addition, KIPP set up hotlines to help families procure groceries and create workspaces. Teachers got professional development on online instruction and “nurturing students from afar.” From Tapinto:

“We have students who are as young as five years old who are getting on these platforms and students up through 12th grade,” Belcher said. “The good news is, our kids use computers in their classrooms in all of our schools as part of our regular instructional program so we felt really confident that students would be able to navigate some of the software programs that we’re using.”

At Uncommon Schools’ North Star Academy, the K-8 Remote Learning Hub and High School Program intends to “ensure that students are actively engaging with their academics and continuing to learn new content so that we are all ready to hit the ground running when we are able to join back together as a community.” Broad-band access and laptops are provided to all students.

In contrast, the DOE top guns told Mooney that online instruction was “all new” to teachers, that “we’re just trying to get them into the ready mindset,” and “I’m optimistic, John. I don’t see us going backwards.”

Maybe not backwards but awfully slow.

[Aside: Throughout the interview Repollet and Eno refer to current circumstances as a “paradigm shift.” They should read up on their Thomas Kuhn. A paradigm shift is a profound change in a fundamental model, a revolution in scientific thinking that permanently changes all the rules. In this context, we would not resume brick-and-mortar classrooms, or at least online instruction would play a primary role, as would parent oversight of learning. Not happening. So it’s not a “paradigm shift.” Repollet unknowingly corrects himself when he tells Mooney that online instructions “is not going to ever replace the brick and mortar.School provides an opportunity to be empowered. So I think it’s not going to change.”]

3 Comments