Sunday morning Education Secretary Betsy DeVos went on CNN and Fox to tout her belief that all American schools must open for full-time in-person learning in September. Afterwards she was excoriated for both her ignorance and her cavalier attitude towards potential outbreaks among students, teachers, and staff.

.@BetsyDeVosED you have no plan. Teachers, kids and parents are fearing for their lives. You point to a private sector that has put profits over people and claimed the lives of thousands of essential workers. I wouldn’t trust you to care for a house plant let alone my child. https://t.co/Qs0Z7gCnMo

— Ayanna Pressley (@AyannaPressley) July 12, 2020

It’s so easy to beat up on DeVos. (Heck, I do it all the time.)

But right now I’m thinking that DeVos and her boss’s idiocy are a distraction. If our goal is to figure out a way for students to learn during a global pandemic, we’re going about this all wrong.

Let’s face some hard facts in New Jersey. While I have high regard for Gov. Murphy’s stewardship during this crisis, the State Department of Education, during Lamont Repollet’s tenure as Commissioner, was rudderless. Kevin Dehmer, our new Acting Commissioner, isn’t inspiring confidence among the DOE staffers I’ve spoken to. Assistant Commissioner Linda Eno retired in June although she and Repollet are still listed on the Organization Chart.

Like DeVos, the DOE, has a cavalier attitude towards reopening, forcing essential staff to take furloughs just as districts are madly scrambling to finish reopening plans due August 1.

Like DeVos, the DOE has issued guidance that is vague and unhelpful. Worse, it has utterly failed to close the digital divide. Schools shut down in mid-March yet by the end of the term 90,000 students were still without internet access and/or a personal device, disabling them from accessing remote instruction. I can’t think of one reason why the DOE hasn’t filled this gap (except that early in his tenure Repollet dismantled the Office of Educational Technology). C’mon guys! Log on to Amazon or go to Costco and get the damn chromebooks and hotspots for the kids! All districts don’t have George Norcross, Campbell’s Soup, and the Camden Education Fund jointly purchasing internet access and devices for the 70% of Camden students without them. Why is this so hard? Why is the DOE taking its lead from the Trump Administration and labeling itself the supplier of last resort?

NJ Spotlight, which rarely criticizes state agencies, reports today that the DOE’s guidance “leaves many questions unanswered,” “provide[s] no path about how much choice parents and educators have in participating,” and districts “have been left to come up with own criteria.” It’s unclear to superintendents whether the DOE may yet offer some concrete advice “but the department is so far staying mum…As of Wednesday, there has been nothing yet, with the department only repeating that the guidelines have been drawn from input from all stakeholders.”

The abdication of responsibility doesn’t end there because NJ DOE leaders have failed to foster collaboration among districts so we can collectively cull the best possible forms of remote instruction. Instead we genuflect to our anthem of local control even when the victims are children, their families, teachers, and school staff.

Here’s the thing: I think we’re in for a lot of remote instruction for the 2020-2021 school year. I’m no prognosticator but NJ’s coronavirus transmission rate ticked up this week for the first time in a while and, human behavior being what it is, we’re likely to see either a spike of this first wave or a second wave this fall or winter, baring a vacccine or treatment breakthrough. Teachers from coast to coast are worried about contagion, especially those who are older or have underlying health conditions. Parents are worried about sending their kids to school. In Jersey City one-third of parents plan to keep their kids home full-time. In West Windsor-Plainsboro, over 50% will.

Can you blame them?

There’s just too much to manage, especially with our broken national infrastructure of testing and contact tracing. (Last week my family went to Maine, which requires NJ residents to get a COVID test 72 hours before entering. We got tested three days before the trip, good citizens that we are, and were told we’d have the results in 48-72 hours.We got them a full week later.)

Uninterrupted live instruction just isn’t in the cards. A district in Maryland just announced the earliest students will come into buildings is February. While economist Emily Oster notes, “if your kid is healthy and not immunocompromised, then the risks to them are really quite low,” we’re seeing more new cases in young adults, including high school students. Israel was a model of epidemiological rigor, with only 300 deaths, but two weeks after schools reopened in May there was a major outbreak — 130 people in just one school. Contact tracing revealed that the virus was spread by a seventh grader and a ninth grader. South Korea and Singapore are other examples where the disease seemed to disappear only to rebound once people resumed ordinary lives.

This doesn’t mean that no child should enter a school building in September. Instead, I think we need to think in terms of triage: Who is at highest risk of academic regression? Which kids benefit the most from brick-and-mortar settings and which kids adapt more readily to remote instruction? Most importantly, how do schools manage remediation for students behind grade-level or, conversely, student readiness for new material?

Grit your teeth all you want but we have to administer assessments as soon as school starts using no-stakes formative tests like NWEA . After all, kids are coming back with proficiency levels all over the map. For example, this study projects that “black students may fall behind by 10.3 months, Hispanic students by 9.2 months, and low-income students by more than a year.” Other high-risk students are English Language Learners and children with disabilities. In order to mitigate further regression, teachers have to meet students where they are. In order to find them they’ll need the information that assessments will provide.

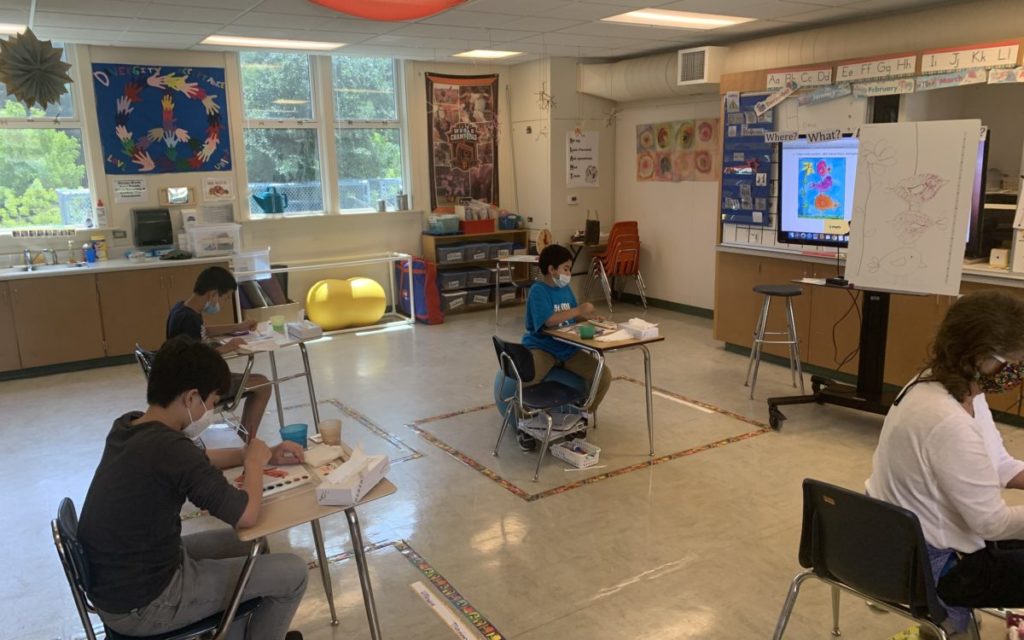

Ideally our younger children — kindergarten through third grade for sure (though fifth grade would be ideal) — will be in classrooms as much as possible with appropriate accommodations: classroom size below 12, lunch eaten at desks, hand-washing every hour, classes held outside when weather permits, recess and other activities that increase risk of contagion put on hold. Students with disabilities should also be prioritized for in-school instruction.

Our older neuro-typical students? If I ran the world — or at least NJ — superintendents and administrators (teachers would have to volunteer or get paid extra because their contracts specify summers off) would be collaborating, maybe within each county, to develop robust online instruction that could be rolled out for all students during periodic closures.

Sound too hard?

Not if it’s out there already.

Example: Rocketship Public Schools, a charter school network with 20,000 students, has made their remote instruction grades 3-5 available to anyone at no cost. Success Academy is sharing its curricula grades K-8 and offering professional development for teachers. Summit Learning (I’ve covered a NJ high school that uses its platform — see here and here) is free as well. TNTP just published this toolkit called “Restart and Recovery: Considerations for Teaching and Learning.” And let’s not forget that frameworks for social-emotional learning, critical during this kind of trauma, are widely available.

Or how about collaborating with some of our top public charter school operators who have comprehensive online learning plans already in place? (Here’s KIPP’S and Uncommon’s.)

Why reinvent the wheel 600 times, each school district on its own? Isn’t this pandemic an opportunity to scale up equity and access in our public education system? Why aren’t districts ahead of the curve sharing their instructional material and reopening plans with other districts that have fallen behind? They’re all our kids, right?

Speaking of avoiding redundancy, is it beyond the realm for New Jersey to detox from the high of home rule and have multiple districts pool their resources — this includes buildings, custodians, even teachers and supervisors — to best serve our kids? What if, say, three districts, all within a 15-mile radius, worked together to accommodate as many students as possible? Among the districts there would be enough facilities to have one grade per school and enough kindergarten teachers to instruct 10 kids in a room. Maybe there’s an especially brilliant 8th grade math teacher who is responsible for a one-hour daily live lesson on Zoom for all students in the collaborative while the other 8th grade math teachers — from all three districts—-work remotely in small groups or one-on-one with students to keep them on track?

What if we broke down those walls and kept them down?

Hey, a girl can dream.

1 Comment