Since the beginning of New Jersey’s chronic fiscal crisis in the early-2000s, there’s been an unending argument over raising taxes on high-earners to mitigate the budget crisis. The argument over high-brackets exists in periods of New Jersey’s growth, like in the mid-2010s and Phil Murphy’s first three budget proposals, and in times of recession, like the Great Recession and today’s Coronavirus Recession.

There are some New Jerseyans who are flat-out conservative and believe creating high brackets is “punishing success” and that it would deter entrepreneurism. But the more significant argument is the intra-Democratic argument between moderates who oppose raising rates due to the pragmatic belief that high rates will induce rich people to leave, and progressives, who insist taxes are marginal costs to already-rich people, that interstate moves are motivated by the lifestyle changes, weather, and family considerations, and that higher-brackets are necessary to reduce racial and social inequality.

In tracking this argument, something I see as incomplete it’s always framed as people leaving New Jersey, or outmigrating from New Jersey, or an “exodus from” New Jersey. Chris Christie simply said, “tax them and they will leave.”

NJ’s newspapers write headlines about David Tepper’s departure, Mercedes-Benz’s departure, Honeywell’s departure, but New Jersey newspapers rarely write stories about a pharmaceutical company opening a lab in Massachusetts, or a bank expanding in Salt Lake City, Dallas, Florida, or Nashville. Yet these events in other states are important for understanding New Jersey’s current economy because a generation ago, those firms would have expanded in New Jersey.

The “tax them and they leave” framing elides the other half of the equation, which is how do high taxes affect the location decisions of businesses and people in other states who could have moved to New Jersey?

Perhaps we don’t consider “New Jersey Avoidance” because it’s difficult to measure and is a non-event that doesn’t generate headlines. Yet it’s a phenomenon that can be inferred by how New Jersey’s wealth, income, population, and jobs growth lag national averages.

Despite the lack of news coverage of New Jersey avoidance, the IRS’s Statistics of Income allows one to infer that the effect is occurring.

Yes, New Jersey’s millionaire population has had large growth (+214% since 2001), but that growth is nowhere near the national average (which was +330%) and is the fourth lowest in the US. Thus, even if NJ’s millionaire population grows, either through businesses not expanding here or individuals not wanting to relocate here, there is an avoidance effect happening that may be more significant than departures.

The Tax Flight Myth

Phil Murphy has also said that “millionaire flight is a myth” and actively campaigned for higher income taxes prior to 2020’s expansion of the 10.75% tax bracket, but his statements are sparse compared to the New Jersey Policy Perspective, an NJEA-funded activist group based in Trenton.

The NJPP is a frequent proponent of raising taxes on the wealthy and has written multiple reports (or “reports”) arguing that it’s a “myth” that millionaire outmigration and that there’s been an exodus of wealth from NJ.

For instance, there’s this 2016 piece “The ‘Exodus’ is More Like a Trickle” written by Sheila Reynertsen.

Several rigorous statistical studies of interstate moving patterns confirm that there is no meaningful correlation between state taxes and interstate moves. For example, a new long-term study of top income-earners found that the vast majority of millionaires don’t move to avoid state taxes. Another study specifically looked at the impact of New Jersey’s 2004 enactment of a higher tax rate on incomes of more than $500,000 and concluded that “the effect of the new tax bracket is negligible overall. Even among the top 0.1 percent of income earners, the new tax did not appreciably increase out-migration.”

More importantly, the amount of new revenue gained from the tax change dwarfed the tax payments that would have been made by those few who left. The estimated revenue lost was less than 2 percent of the overall revenue gained. In other words, New Jersey did not lose money by increasing income tax rates on the wealthiest households.

The argument that the elderly, in particular, flee taxes by moving to lower-tax or no-tax states is also not supported by the empirical evidence. The patterns of state-to-state movement among the elderly have remained relatively consistent over time, even as state tax policies toward the elderly changed significantly across states. If older people who leave New Jersey are heading to popular retiree destinations regardless of tax policy, there is no reason to offer them tax breaks in the hopes that they will stay.

Notice how Reynertsen, just like conservatives, frames the issue as people leaving NJ. There is no contemplation of an avoidance effect.

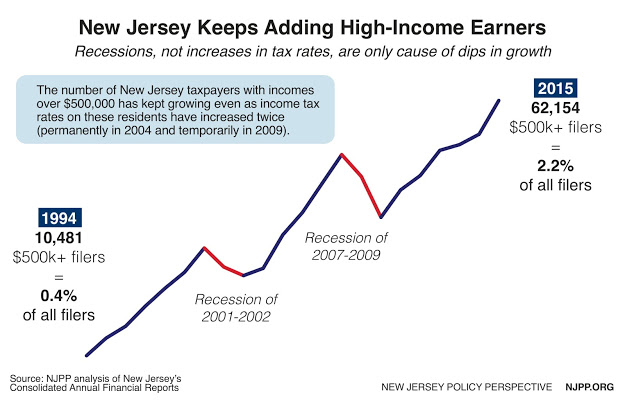

The NJPP’s #1 piece of evidence that high-income outmigration is a “myth” is that despite New Jersey having multiple income tax increases in the last 20 years, the number of millionaires in New Jersey has grown, in raw numbers and as a percentage of the population.

So how can there be an outmigration problem if the population of rich people keeps growing?

Inflation is one factor. $500,000 in 1994 = $800,000 in 2015. Inflation isn’t an obscure thing, but the NJPP ignores it.

And the interstate comparison matters because every single state has had a huge increase in its million-earning population.

The NJPP is a progressive information filtering service, not an objective think tank, and context is to be ignored, manipulated, and switched in the service of whatever progressive cause the NJPP is advocating for. When it suits the NJPP, they use nationwide and regional comparisons, but when interstate comparisons would undermine the progressive case, the NJPP doesn’t.

One of the Slowest Growth Rates for High-Income Tax Filings

The IRS’s Statistics of Income does not go as far back as 1994, and it does not provide data on $500-$1 million earners and >$1 million earners for the years 2002-2009, but a comparison of 2001 and 2018 data reveals how much the growth of NJ’s high-income population has lagged the nation’s.

|

2001 |

2018 |

Increase |

|

|

NJ Over $1 mil |

10,499 |

22,440 |

213.7% |

|

NJ $500-$1 mil |

19,290 |

49,700 |

257.6% |

|

US Over $1 mil |

193,798 |

541,410 |

279.4% |

|

US $500-$1 mil |

358,008 |

1,101,480 |

307.7% |

To put it another way:

|

Percentage of $1 million returns from NJ in 2001 |

5.42% |

|

Percentage of $1 million returns from NJ in 2018 |

4.14% |

Because if you look at the increase in the number of millionaires nationwide, NJ’s increase has lagged the national average. New Jersey’s population of $1 million earners only grew at 76.5% of the national rate.

NJ’s increase in people earning over $1 million was the fourth smallest in the US.

New Jersey’s increase in people earning $500,000-$1,000,000 is the fifth smallest in the country.

It’s true that NJ’s overall population has grown very slowly, but NJ’s share of the total population didn’t show as large a lag against national growth. In 2001, New Jerseyans had 3.1% of total tax returns in 2001 and 2.9% of total returns in 2018. NJ’s growth in overall population was 9th slowest in the 2010s, but not 4th-5th from last.

It is difficult to disentangle overall slow economic growth from low growth of high-income populations, but I think I think they are codependent. I cannot prove how much of this effect is due to taxes, but other high-income tax states like New York and Connecticut have also seen slow growth, although, to be honest, other high-income tax states like Iowa, Minnesota, and California have gotten strong growth.

I am not aware of polling of ultra-rich people on residential decisions, but there is a lot of evidence they are more fiscally conservative than non-rich people. A large body of polling evidence certainly shows regular people care about taxes as well. A 2014 Monmouth University poll found that New Jerseyans who wanted to leave were much more motivated by cost of living and taxes than any other factor, with higher-income people more likely to say taxes. Gallup has found that people in high-tax states were much more likely to want to leave than residents of moderate-tax and low-tax states (residents of moderate-tax states were not more likely to want to leave than residents of low-tax states).

Based on the conservatism of high-income people and polls of the general population, I think one can infer that high-income people can be intolerant of taxes enough to take taxes into account in their location decisions.

Can Income Migrate?

A secondary New Jersey Policy Perspective claim is that income can only rarely leave a state.

Again, this is Sheila Reynertsen:

The vast majority of people actually don’t take their income with them to a new state – because they can’t. When people make an interstate move, they usually leave their job to take another, and the income they made in their previous job typically goes to the person who replaces them. That state income essentially stays put, which explains why New Jersey’s overall income reported each year grew significantly at the same time we “lost” that $18 billion.

The same holds true for business owners if they leave the state. The money their business made goes to the new owner of the business if the old owner sold it, or other in-state businesses that pick up the customers of the one that left. If a doctor or a plumber or the owner of a restaurant leaves New Jersey, the patents and clients and customers don’t leave too.

For those moving out of state upon retirement, it is equally misleading to claim that New Jersey’s economy loses income equal to the person’s pre-retirement salary, because their income also would have declined if they had retired in New Jersey.

The above is partly true. The vast majority of people can’t take their income with them to a new state, but that doesn’t mean the vast majority of income can’t be moved, because wage income isn’t the “vast majority” of income.

For NJ’s total $426.7 billion in total income in 2018, $289.1 billion was “Salaries & Wages,” or 68%. The rest is interest, capital gains, S-corp profits, dividends, royalties, pensions, Social Security, alimony etc. I don’t know what percentage Sheila Reynertsen considers a “vast majority,” but 32% of NJ’s income is non-salary income and that amount can’t be dismissed.

Whatever threshold the NJPP uses for the qualifier “vast majority,” what is indisputable is that higher income people have more non-salary income.

For New Jerseyans making under $200,000 a year, wage income is 75% of their income, but for New Jerseyans making over $1 million a year, wage income is only 39%. The rest is other types of income that is portable.

For New Jerseyans making $500,000 to $1 million, wage income is 62% of their total earnings.

For New Jerseyans making $25,000-$50,000 a year, non-wage income is still 19% of earnings because that stratum includes people getting retirement income.

Sometimes non-wage income might be hard to take out of New Jersey, like some S-corp profits, but sometimes wage income is portable too, like in the following scenarios:

-

the person becomes a remote worker.

-

the person moves to another state and becomes a commuter to a NJ-based job.

-

the business itself moves.

So yes, it really is money lost to New Jersey when people leave.

Remote working was becoming more common even prior to Coronavirus, but its new acceptability presents a challenge to New Jersey. High-income workers are more likely to be able to work remotely than middle-income and low-income workers. Given how low NJ’s income growth already is, if remote working frees only a few thousand high-income workers from New Jersey or allows New Yorkers and Philadephians to “suburbanize” outside of the region to Florida or to resort towns or wherever they grew up originally, remote working stands as a problem for New Jersey after the Coronavirus-flight from New York City ends.

Conclusion:

It is true that New Jersey’s population of high-income people has grown much faster than New Jersey’s overall population, but that outsize growth has taken place nationally and New Jersey’s high-income population growth is one of the slowest in the United States.

The state’s economy and income do grow — and the millionaire population grows faster than NJ’s general population — but the growth is insufficient to get New Jersey out of its fiscal vise of debt payments consuming a gradually larger percentage of the budget. Indeed, for all the relief about the FY2022 budget, the spending increases are powered by borrowing and federal aid. New Jersey’s revenue is only up 2.4%.

In the short term, raising taxes on rich people would alleviate one year’s budget crisis, but in the long-run, reduce NJ’s income growth, revenue growth, and necessitate another round of tax increases.

Also, word to the media, be careful with citing New Jersey Policy Perspective papers as authoritative.

—

Note 1: NJ’s Adjusted Gross Income was $406 billion in the year analyzed. I used total income here because I want to discuss what percentage of it is possessed by various income strata. If I considered the deductions people qualify for like the Adjusted Gross Income uses, it would not give as accurate an amount.