When Gov. Phil Murphy signed a new teacher health care law in 2020 called Chapter 44, leaders of the New Jersey Education Association celebrated but school districts and NJ School Boards Association were a bit leery: after all, the new law lowered teacher contributions to their health care plans by thousands of dollars and districts were supposed to realize savings by a switch to less generous health care benefits. The Governor and NJEA predicted NJ districts would save 300 million dollars, but who really knew how the math would work?

Turns out many school districts are losing money, with no recourse but to raise property taxes or make internal budget cuts. And, once again, what’s a win for NJEA leaders— controlling top education appointments

, strangling public charter school growth, pushing lengthy COVID school closures— is a loss for NJ residents, especially children and families.

Let’s look more closely.

Back during the Christie Administration, the Democratically-controlled Senate and Assembly passed a bill called Chapter 78, which raised teacher contributions to health care benefits. Under the previous law, teachers, paraprofessionals, and administrators made a 1.5% contribution of their salary to their benefits; under Chapter 78, contributions ranged from 3% to 35% of total healthcare premiums. This resulted in big savings for districts (at the time, districts paid about $25K per employee for benefits) but losses for staff members, sometimes resulting in a net loss of take-home pay.

Once Chapter 78 sunsetted (one year after everyone had been phased into the new plan), local unions were free to re-negotiate health care benefits. But those savings had been baked into district budgets. While some school boards made big concessions, others didn’t.

In comes Chapter 44, which was intended to save everyone money—staff, school districts, taxpayers—by lowering staff contributions from Chapter 78’s 3% to 35% to a new ladder of 1.7% to 7.2%. It was also supposed to lower district costs by switching to less generous plans that reduced out-of-network reimbursements and, thus, lowered statewide school health care costs. The Murphy Administration estimated we’d save $300 million a year.

Not so much.

As NJ School Boards Association warned back in 2020, “the reality is that premium costs will continue to rise, and, in the newly created plans, employee contributions are tied to employee salaries, not to rising premium costs.”

- According to North Jersey Media, the state projected that Ridgewood Public Schools District would save $4.7 million a year. It’s saving $27 thousand.

- Warren Hills saw health care costs rise by $197 thousand.

- Gloucester County saw health care costs rise by $260 thousand.

- Franklin Township (which filed a complaint, calling Chapter 44 an unfunded mandate) saw health care costs rise by $1 million a year. “If every employee of the Franklin Township Board of Education switched to the new plan, it would result in employees and the Franklin Township Board of Education paying a combined $1,131,967.68 more,” the Somerset County district said in its complaint.

All in all, 159 districts (these are current numbers) say Chapter 44 is, contrary to expectations, not saving them money but costing them money, forcing them to raise property taxes and/or make budget cuts.

Health care costs are a big part of a school district’s budget. Case in point: Montclair Public Schools, which projects that in 2022-2023 employee benefits will cost $23,430,673, or 17% of its budget. That’s a 20% increase in employee benefits in three years. While there’s no straight line between these losses and the 83 staff members who got lay-off notices this week, it’s hard to imagine that Chapter 44 didn’t have any impact on what Superintendent Jonathan Ponds calls the year-to-year “cycle of budgetary trauma.”

Here’s another example from North Bergen Superintendent George Solter: If a $90,000-a-year employee’s total medical and prescription benefit package was $36,000, the employee’s contribution was $10,000 and the district $26,000. Now, the district may be saving $1,000 under the new plan but the employee’s bill dropped by $4,000, a net loss for the district.

There’s hope for a compromise: the law requires that by July 31, 2023 the state actuary will submit a report validating that districts have saved at least $300 million. If it’s less than that, the state can make changes to make up for that shortfall, like increasing employee contributions.

The problem is that’s a political decision, not a mathematical one.

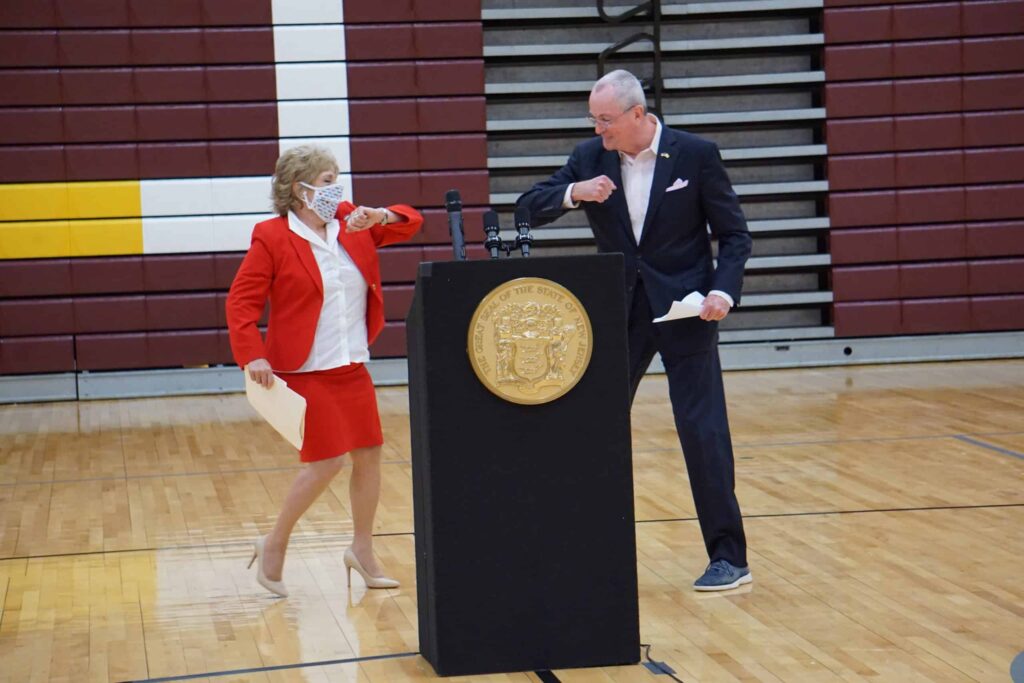

“I am proud to sign this bill into law and at long-last provide relief for our educators from Chapter 78,” said Governor Murphy in 2020.

“This law is a win-win-win for NJEA members, our students and New Jersey residents,” said NJEA President Marie Blistan.

Not so much.