Laura McKenna is an education writer based in New Jersey. You can find her at www.lauramckenna.com. This was originally published at her newsletter, Apt. 11D.

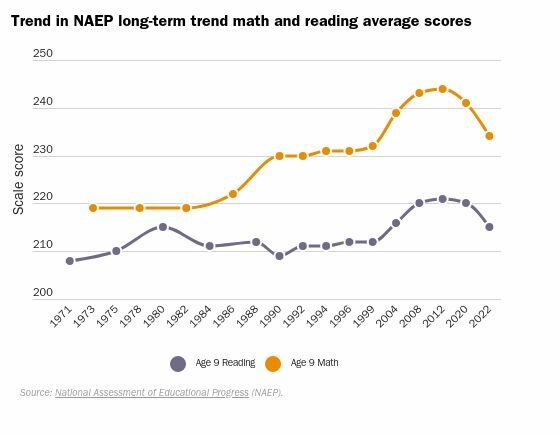

Last week’s headlines screamed “Pandemic Erased Two Decades of Progress in Math and Reading.” According to results from the latest National Assessment of Educational Progress tests, also known as the NAEP, the reading and math scores of a randomized sample of 9-year olds dropped to levels from two decades ago. Students of color experienced the largest drop in scores – Black students lost 13 points in math, while white students lost 5 points.

Pre-pandemic, reading and math test scores in this country were not awesome. Reading instruction and math instruction has sucked for a long time; too many kids were not proficient. It’s shameful. But now, things got worse.

While the NAEP results do not prove causation — these test results do not prove that school closures, as opposed to other COVID horrors, caused this drop — plenty of other studies do show that students who experienced the least amount of in-person education suffered the worse learning loss. Whatever the cause, test scores dropped, and that’s what is important.

First let me just state the obvious: Reading matters. Math matters. Kids that are not on grade level for those basic educational needs are statistically more likely to dropout of high school and live under the poverty line. An individual without a high school diploma earns around $31,000 per year, while someone with a BA earns around $65K on average. Other research shows the connection between literacy levels and income. To improve equity in this country we must address the massive educational inequities first.

Though I am still extremely angry that our nation failed to protect the interests of young people during the pandemic, I do think that we should move forward and focus on remedies right now. How do we help kids catch up, given the massive body of research that shows that kids who fall behind, rarely catch up?

Kids catch up when given massive amounts of high quality, intensive, one-on-one tutoring. However, kids don’t get that help, because it’s extremely expensive. The problem isn’t with children’s brains. The problem is political.

In the past couple of years, the federal government gave $190 billion to our nation’s schools for COVID relief. That money was supposed to help kids, who spent far too long out of classrooms. That’s a hell of lot of money that could have been used for tutoring and summer school. Jill Barshay in the Hechinger Report had a great piece last year on the research that shows that high-dosage tutoring makes a difference

. I liked her article so much that I read parts of it out loud during the comment section of a local board of education meeting. Trouble is, it never happened.

They don’t really know what happened to all those billions of dollars of Covid money, but there’s a lot of evidence that the money never made its way to kids and tutors. In my own school district, they offered help to students who couldn’t learn remotely, with remote summer school. Not surprisingly, few students agreed to sign up for those classes. During the school year, they offered some extra help for a select group of students, but instruction wasn’t individualized and the classes were offered at 7am. Instead, our district used the ESSER money for fixing the school building, paying teachers to attend professional development sessions, and buying air filters. Because we live in a privileged community, parents hired $100-per-hour tutors to help their kids, but this solution is not available to everyone.

Theoretically, Congress and Biden could get together and send schools another pile of cash, this time with VERY rigid parameters in place for how to spend the money. Getting this money out of Congress for a second time is, of course, a political fantasy, but let’s just imagine that schools got that money. Even with another $100 billion, students would still not get that much needed help, because there’s nobody to do that job. We barely have enough teachers in some parts of the country; good tutors are even more scarce.

Last week, I read Robert Pondiscio’s profile of an extremely strict charter school system in New York City, The Success Academy. Kids have to walk the hallways in lines, wear uniforms, and even sit in a particular way in the classroom. Parents are expected to fill out reading logs with their kids and regularly communicate with teachers. Students who fail to meet expectations are held back, sometimes multiple times. But the school works for those who can jump through the many hoops. Students there – nearly all of whom are low-income minorities – score in the top percentile for reading and math tests, while only a 1/3 of similar kids are on grade level for those subjects. Their graduates end up at places like Harvard and Yale.

The methods at the Success Academy are extreme and can only work for a very specific type of kid with a very specific type of parent, but maybe there’s something that they’re doing that can be emulated by public schools. As we return to more traditional methods for reading – phonics is back! – maybe it’s time to revisit other practices. Maybe we should have higher expectations for behavior.

Or we can just raise the cap on charter schools and allow Eva Moskowitz to expand her empire.

I think it’s time to entertain all possible solutions — new funding for tutors, retraining teachers for evidence-based practices, expanding the amount of time in school, expanding high quality charter schools to meet the demand, bringing in new corporate donors, blurring the lines between high school and community college. I’m up for anything, because the status quo is unacceptable.